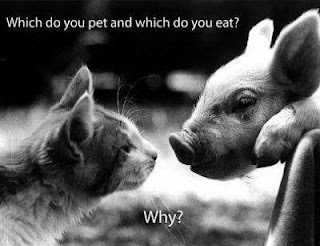

There are essentially three perspectives regarding the moral status of animals: Animal welfare, Human dominion, and Animal rights.

There are essentially three perspectives regarding the moral status of animals: Animal welfare, Human dominion, and Animal rights.Animal Rights

The final position regarding the rights of non human animals is called the Animal rights position. This position contends that animals have moral rights. In fact this position argues that animals have the same moral status as humans. According to this perspective, human animals and non human animals are not to be placed in different moral categories. It further argues that when individual have moral rights, we cannot treat them as means to our ends. Therefore, animals should not be treated as means to human ends.

This position opposes most of the traditional uses of animals including those items listed as permissible under the Animal welfare and the Human dominion position, as well as issues such as the consumption of animal by products such as milk and eggs, captive breeding programs for endangered species, and finally the keeping of pets.

The philosophical underpinnings of the Animal rights argument focuses upon the contention if you have rights then we cannot justify harming you because the benefits to us outweigh the harms done to you. This would constitute abuse for the human animal and in turn it would also constitute abuse to the non human animal. Further, some non human animals have mental lives similar to those of some humans such as very small children. In addition, the argument proposes that if we recognize rights for all humans including very small children then we should also recognize the rights for those types of animals. Finally for those animals, we cannot justify harming them just because the benefits to us outweigh the harms to them.

A contemporary representative of this perspective is seen in the work of Peter Singer. Singer’s most prominent work was entitled Animal Liberation and profoundly propelled the animal rights movement in Europe and America. For Singer, to distinguish between the rights of non human animals and those of human animals has the serious consequence of leading to a distinction between the rights of various categories of human animals.

Singer proposes the hypothetical consideration of a human animal encountering an extra terrestrial. He contends that in this circumstance we would not be justified in assigning the extra terrestrial a lesser moral status because they do not possess certain characteristics of human animals, such as the possession of human DNA. He argues the same regarding the moral status of the non human animal. Simply because the non human animal does not possess some characteristic possessed by the human animal does not mean that the non human animal is to be granted lesser moral status.

Singer also argues against the use of categories or properties such as rationality, autonomy and the ability to act morally since to utilize these types of categories would potentially lead to the justification of such practices as racism and sexism. Singer cites the racist who contends that all members of his race are intellectually superior and more rational than members of other races. The racist therefore assigns a greater moral status to the members of his race than to the members of other races despite the fact that the racist is wrong in his contention of the intellectual and rational superiority of his own race. The same could be said of the individual who justifies a sexist viewpoint on the same erroneous factual grounds.